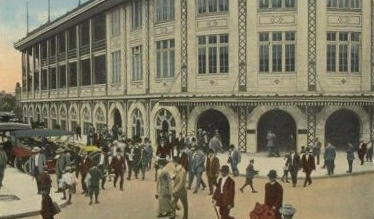

Today the Pittsburgh Pirates baseball team plays its games in a still new stadium on the "Norside" of town, across the Allegheny River from "Dahntawn". From the middle of the 1970 season until 2002, the Pirates played their home games in Three Rivers Stadium. This venue was shared with the football Steelers, in the huge bowl-shaped arena that became the vogue in the 1970s. But the ball park I remember best, and the one that will always be best in my memory was Forbes Field. It too was new once, way back in 1909. Located way out in the Oakland section of town, it sat along Stennett Street, not too far from Forbes Avenue and the University of Pittsburgh's skyscraper Cathedral of Learning.

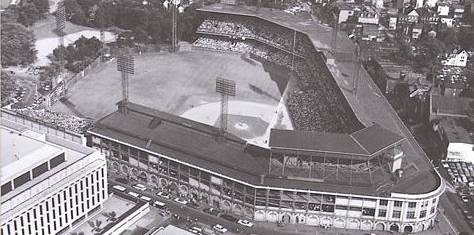

Forbes Field, named for British General John Forbes, or at least for the Avenue that in turn took its name from the General, was typical of the ball parks of its era. Just as the later Three Rivers Stadium was much like Veterans Stadium in Philadelphia, Riverfront Stadium in Cincinnati, and a host of other baseball-football arenas, Forbes Field was similar in design to Tiger Stadium in Detroit, Shibe Park (later renamed Connie Mack Stadium in Philadelphia), and Crosley Field in Cincinnati to name but a few. It wasn't symmetrical. Originally the double-deck stands for seating ball fans extended out the first and third base lines. As the team owners prospered, the stands along the first base line were extended to the outfield, eventually reaching behind the right-center field fence. There were open "bleachers" along the left field line, so named because they were not covered over, and fans would bake in the summer sun. There were no seats behind the ivy covered brick walls in left and center field. A huge scoreboard stretched from the left field foul post towards center field. Nothing electronic in those days. Balls, strikes, outs, runs, hits, errors - all were shown by numbered signs that "the guy who worked in the scoreboard" hung on hooks to be seen by fans. Not only the current Pirate game was reported on the scoreboard. Scores of all the other games being played that day were reported as well. There were always a few openings in the board, so the guy (or guys?) who worked in there could watch the game. How else would they know what numbers to hang up? Another person who worked inside the scoreboard was the organist, who constantly played rally-rousing music. If a batted ball hit the scoreboard and fell back on the field it was still in play. If it went into the scoreboard it was a ground-rule double.

It was 1954 when my dad took me to my first ballgame there. We would go to five or six games a year, often to a "double-header" which were pretty common on Sundays. Two games for the price of one. Today's big player salaries don't allow that anymore. Players would probably go on strike if they had to play two games in the same day. In the 50's, the leftover Pennsylvania "Blue Laws" prohibited Sunday baseball after 7:00 PM. So if the second game of the double-header ran late, it would be suspended at 7:00, and finished on some other date. With the departure of home run king Ralph Kiner to the Chicago Cubs, Pirate baseball in the early 50s didnít have a lot to cheer about. Curt Roberts, who was the first black man to play ball for the Pirates, and twins Johnny and Eddie O'Brien were the earliest Pirates I rooted for. Fred Haney was the manager, and the Pirates always finished last. That's just the way it was, at least for several years back then. Sluggers "Big Klu" and Frank Thomas were bright spots until they too were traded away. (Does anyone remember the day Frank Thomas came to Crafton High? 1958 maybe? Donna Dagg -CHS 61- knew him and brought him to school one day.) But the team was slowly building to the one that would surprise Pittsburgh and the baseball world in 1960, when they would get back at those dreaded New York Yankees for the 1927 World Series.

The distance to the right field foul post was only 300 feet, one of the shorter fences in the National League. To compensate, a high wire fence was built that extended some distance out from the foul post into right field. This prevented a lot of "cheap" home runs, as the ball had to go over this fence to be a home run, not just land in the stands behind the wall. A ball that hit the fence and dropped back on the field was still in play. As if making up for the short right field line, the distance into dead away center field at Forbes was 465 feet. The wall from the right field line met the wall from the left field line at a point there. It took a mighty blast to send a ball to the center field wall, a blast that would have been a home run in almost any other ball park, or if it had gone a bit left or right instead. The Pirates were so confident there wouldn't be many balls hit to dead center that the Batting Cage was stored there. This cage would be wheeled into home plate before games while the teams took batting practice to prevent foul balls being hit into the stands, then it would be wheeled back out to center field. I remember one time when a fly ball landed on top of the batting cage and stuck - wish I remembered who hit it. I think that was called a "ground rule double." I'm sure the umpires made up a rule to cover that one.

We almost always took the trolley to Forbes Field, parking the car downtown where parking lots were cheaper and not the hassle of finding a parking place in Oakland. It was a short walk from the "car stop" to the ticket windows along Stennett Street. I think General Admission tickets, and that's what we always got, were $3.00 in the 50ís. We usually sat in the upper part of the lower level stands out past first base. I recall one game where we got upper level tickets, but couldnít see much because one of the huge steel beams that supported the roof was right in front of our seats. As I got older and would go to games with a buddy, we usually got seats in the upper deck above the right field wall. You could almost see home plate from there, but you got to talk to Gus Bell and Sid Bream and other Pirate right fielders.

Another thing I remember was the net behind home plate. A wire screen fence ran behind home plate. Fans could see through, but fouled-back baseballs couldnít get through to hurt someone. A big net was attached to the top of this fence and was tied off to the upper deck. A foul ball that went back and landed on the net would roll up until gravity stopped it, then roll back down and drop to the field where the bat boy would scoop it up and give it back to the umpire. When this happened, everybody in the park would go, "Whoooooooooooooooooooooo! Whoooooooooooooooooooo!" as the ball rolled up the net and then back down again. Like many kids, I took my ball glove to the field, at least when I was younger, always hoping that a foul ball would come my way and I would make a memorable catch. Of course it never happened, but the hope is part of the magic of baseball.

Today Forbes Field lives on only in the memories of thousands of Pittsburghers and other baseball fans who went to games there. But a few bits of it are still very real. A small section of the old stone left field wall still stands among the new University of Pittsburgh buildings which were built in its place. This is the part of the wall where Bill Mazeroski's "miracle home run" left the park to beat the Yankees in the bottom of the ninth of the seventh game of the 1960 World Series. What a monument! A Pitt building also covers the spot where Forbes Field's home plate sat for those 61 seasons, but home plate is still there, proudly mounted in the floor of the building for all to still come and see. So you see, Forbes Field was baseball to me, as the stadiums that have succeeded it were, are, and will be to other fans of our still great "national game."